Klaus Hübner, 88, spent his childhood in eight orphanages in Berlin during World War II. Today, his home is a museum of memories

In August of 1977, as the world mourned the loss of Elvis and headlines read “The King is Dead,” Klaus Huber found himself at the beginning of a 48-year journey, gradually shaping a home that reflects the life he has lived.

Upon entering home, he greets me with a thick German accent and offers to make me crab cakes and eggnog — the combination you didn’t know you needed at 12 oclock on a Friday afternoon. A tool maker by trade, he still sports his thick glasses as an ode to another time.

“Making Tracks for Spicy Traxx Crab Cakes” Culinary SOS article by Noelle Carter was published in 2008. Klaus keeps this clipping to make his weekly crab cakes.

Katherine, Klaus's friend of 24 years, joins us. She often comes over to care for Klaus often acting as the mother figure he never had.

Now 88 years old, Klaus spent his childhood between eight different orphanages in Berlin during World War II.

While Klaus himself never met his father, he was able to learn about his father's role as a wartime photographer and painter. Klaus is a painter himself, and attributes this skill to him.

When looking around his home, my eyes are met with a portrait of Eva Braun, Hitler's wife and companion in death.

Klaus proudly shows me a painting of the church near the home he shared with his foster mother before she died when he was five. Sent to Poland during the bombing of Berlin, he later returned to find the church and the entire street reduced to rubble. The colorful painting, born from memory, stands in striking contrast to the black-and-white photograph of the church as it once stood.

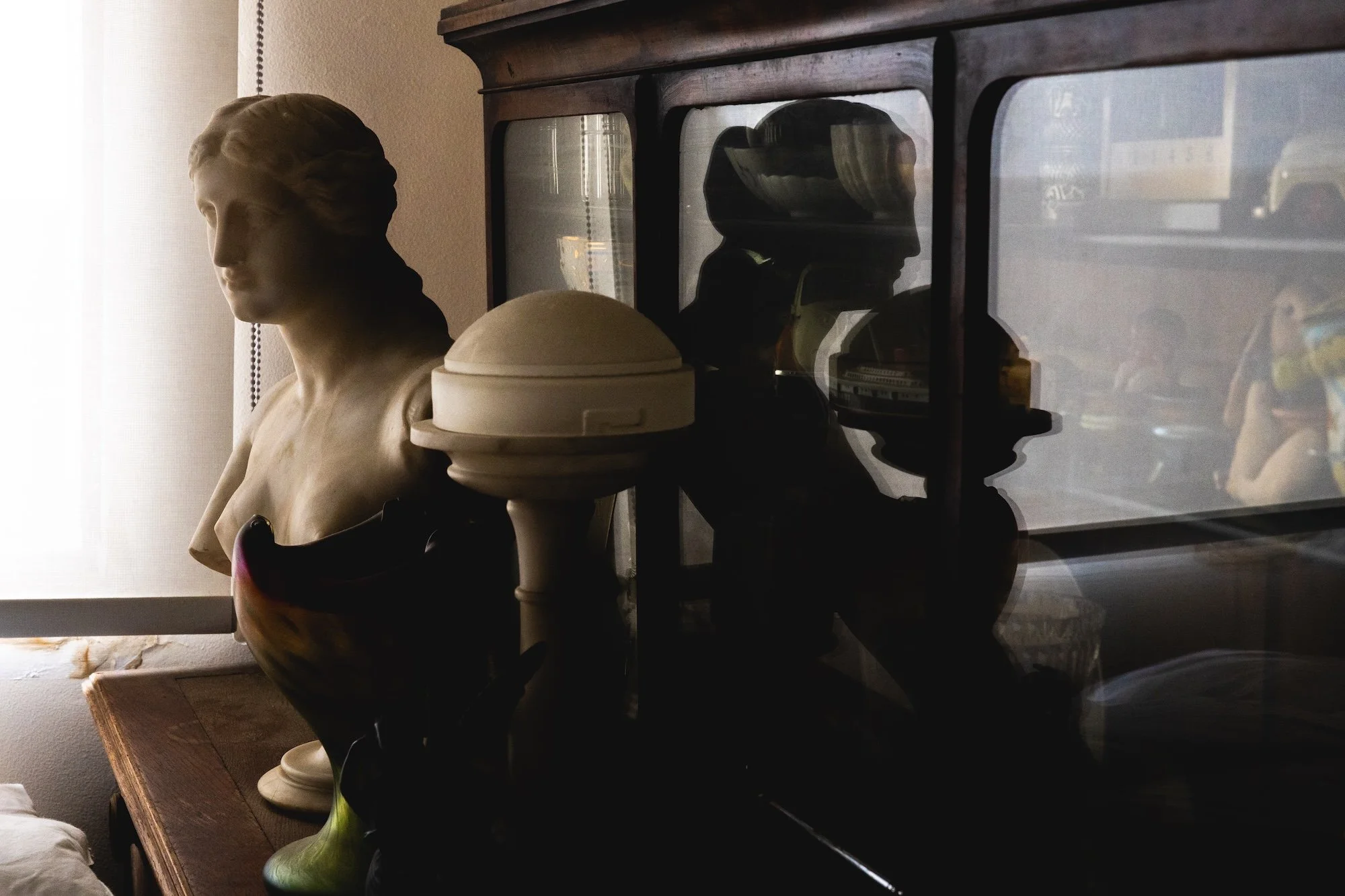

Every object in Klaus’s apartment appears to hold a story.

Tucked into the corner of his room is a porcelain statue from Dachau, made in a Nazi-controlled factory near Munich that relied on slave labor from the Dachau concentration camp.

Klaus pulls out a stack of handmade postcards, some bearing his paintings, others his photographs. Among them is a postcard that Klaus took of the site of James Dean’s infamous car crash, alongside another showing the wreckage itself.

Klaus loved James Dean. The memorabilia scattered throughout his apartment made that apparent. When I asked him why, he simply said, “He was my idol. Some children loved singers; I loved James Dean.” That reverence, carried decades later, is a stark reminder of how deeply a life can resonate—especially with a child who had so few people to look up to.

I often wonder why some of the most adverse stories are also the most compelling. I can only speculate, and be grateful for the chance to hear them.

All images and text were created with the subject’s knowledge and consent.